EVOGENIO® - Evolutionäre Kunst

Dr. Günter Bachelier - My Evolutionary Art processes

The second level of my artistic

work is the methodical level, where I transfer evolutionary concepts

and

methods to develop evolutionary art processes that enable me to create

non-representative works of art that fit my aesthetic preferences. I

view an art process as a sequence of actions by an artist or group of

artists whose outcome is a work of art (image, sculpture, ...) or the

process itself is a work of art (performance, dance, ...).

The second level of my artistic

work is the methodical level, where I transfer evolutionary concepts

and

methods to develop evolutionary art processes that enable me to create

non-representative works of art that fit my aesthetic preferences. I

view an art process as a sequence of actions by an artist or group of

artists whose outcome is a work of art (image, sculpture, ...) or the

process itself is a work of art (performance, dance, ...). In this context, an evolutionary art process can be defined as an artistic process where the three evolutionary concepts population, variation and selection are used. This does not necessarily mean that the whole process is computerized, or even that a specific evolutionary algorithm is incorporated, because evolutionary art can be done with paper, pencil and a dice. For instance, William Latham was doing evolutionary art on paper, long before his ideas were converted into a computational approach {Todd1992}. Such a definition includes cases where an implemented evolutionary algorithm is only a part of the whole process, specially if the outcome of the algorithm can be optimized by the artist. If the desired output of an art process is a complex image, it is natural to use the aid of computers to generate image individuals, otherwise the change of generation would take too long. The resulting evolutionary art process might be style and material independent.

The background for this development dates back to around 1995, when my scientific interests shifted from Artificial Neural Networks {RitterMartinetzSchulten1992} and specially self-organizing maps {Kohonen1995,Bachelier1998b} to Evolutionary Algorithms and particularly Evolution Strategies {Rechenberg1994,Bachelier1998a, Bachelier1999}. I first became aware of Evolutionary Art when reading the exhibition catalog of Ars Electronica, 1993 about Artificial Life and Genetic Algorithms {AE1993}. I realized immediately that this could be a crossroads, a junction, bringing together my research and artistic interests.

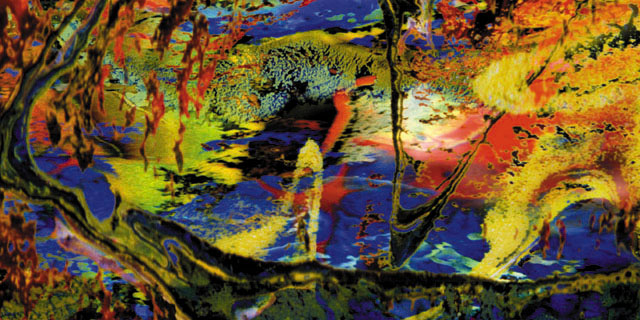

In the first stage I developed an integration of my conventional art process, (self-organizing painting), and an evolutionary art process that uses the basic concepts: population, variation and selection. I used the digital images in my archives for the initialization of the whole of my early evolutionary art runs and I evolved these images over some years (see fig. 1 for example).

Fig. 1: Image individual from the end of my first evolutionary art phase: E-2001-15

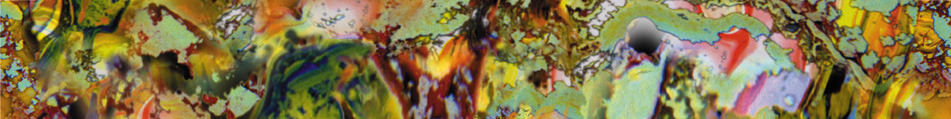

I also used the results for post-processing operations -- such as the creation of abstract panoramas (see fig. 2) which were developed until 2003. They can be viewed on the web (http://www.vi-anec.de/Trance-Art/Gesamt-Panoramen.html}) with a specific panorama viewer. A physical transformation of this kind of art is difficult because panoramas often have a height:width proportion of 1:10.

Fig. 2: Example of an abstract panorama: P-2000-017

Around 2002, I realized that this kind of evolutionary art process was ending. So, in the context of my contrast aesthetics, I began to play with the idea of how to combine contradicting approaches (such as geometric, constructive and concrete art) with the images derived from the non-representational art of self-organizing painting. The combination of geometric shape and non-representational content opened a new dimension to my work and the combinatorial properties of evolutionary art were suitable for exploring this new dimension.

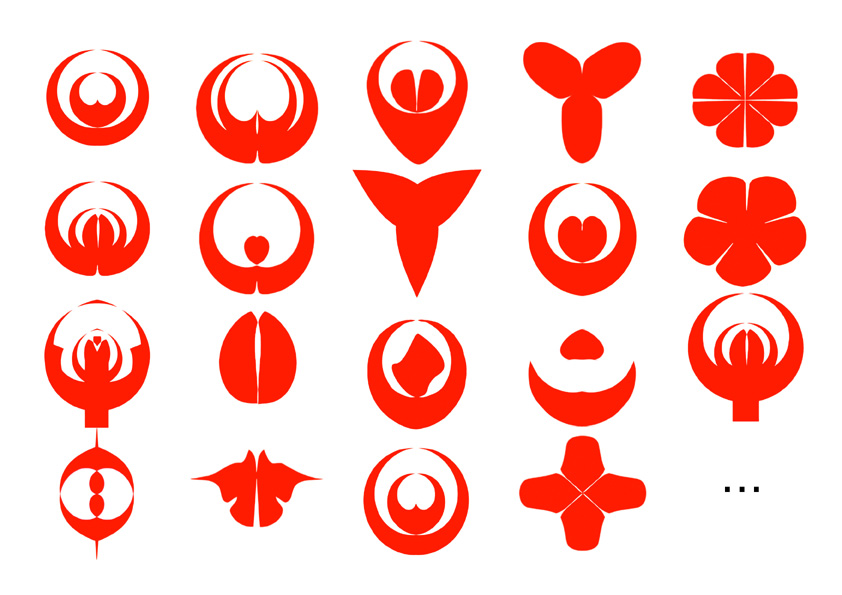

Geometric forms naturally lead to questions about symmetry, so I combined this development with the wish to work with biomorphic shapes by applying the supershape formula {Gielis2003} in many of my new works. Fig.3 shows some examples from the repository of masks generated from supershapes.

Fig. 3: Examples of supershape masks

References

- Günter Bachelier. Einführung in Evolutionäre Algorithmen. Tectum-Verlag, Marburg, 1998.

- Günter Bachelier. Einführung in Selbstorganisierende Karten. Tectum-Verlag, Marburg, 1998.

- Günter Bachelier. Fitness-Approximationsmodelle in Evolutions-Strategien. Tectum-Verlag, Marburg, 1999.

- C. Braun, M. Gründl, C. Marberger, and C. Scherber. Beautycheck - Ursachen und Folgen von Attraktivität. Technical report, Lehrstuhl für Experimentelle und Angewandte Psychologie Universität Regensburg, 2001.

- Karl Gerbel and Peter Weibel, editors. Ars Electronica 93: Genetische Kunst - Künstliches Leben, Linz, 1993.

- Museum Ostwall Dortmund, editor. Informel Bd.1: Der Anfang nach dem Ende. Museum Ostwall, Dortmund, 2002.

- Museum Ostwall Dortmund, editor. Informel Bd.2: Begegnung und Wandel. Museum Ostwall, Dortmund, 2002.

- Museum Ostwall Dortmund, editor. Informel Bd.3: Die Plastik - Gestus und Raum. Museum Ostwall, Dortmund, 2003.

- Museum Ostwall Dortmund, editor. Informel Bd.4: Material und Technik. Museum Ostwall, Dortmund, 2004.

- Johan Gielis, editor. Inventing the Circle - The Geometry of Nature. Geniaal Press, Antwerpen, November 2003.

- Branko Grünbaum and Georey C. Shephard, editors. Tilings and Patterns. Freeman, New York, 1986.

- Hans Hartung and Ulrich Krempel. Hans Hartung - Malerei, Zeichnung, Photographie. HWS Verlagsgesellschaft m.b.H, Berlin, 1981. Ausstellung in der Städtischen Kunsthalle Düsseldorf und der Staatsgalerie moderner Kunst München.

- Marika Herskovic, editor. American abstract expressionism of the 1950s - an illustrated survey with artists’ statements, artwork, and biographies. New York School Press, Franklin Lakes, NJ, 2003.

- Rufus A. Johnstone. Female preference for symmetrical males as a by-product of selection for mate recognition. Nature, 372:172–175, 1994.

- Teuvo Kohonen. Self-organizing Maps. Springer, Berlin, 1995. 3rd edition published April 2006.

- Willy Rotzler. Konstruktive Konzepte. Eine Geschichte der konstruktiven Kunst vom Kubismus bis heute. Zürich, 3nd edition, 1995.

- Ingo Rechenberg. Evolutionsstrategie ’94. Frommann Holzboog, Stuttgart, 1994.

- Helge Ritter, Thomas Martinetz, and Klaus Schulten. Neural Computation and Self-Organizing Maps: An Introduction. Addison-Wesley, Bonn, 1992.

- R. Thornhill and S.W. Gangestad. Human facial beauty. averageness, symmetry and parasite resistance. Human Nature, 33:64–78, 1993.

- Stephen Todd and William Latham. Evolutionary Art and Computers. Academic Press, Winchester, UK, 1992.

- Kirk Varnedoe and Pepe Karmel. Jackson Pollock. Tate Publishing, London, 1998.

- E. Voland and K. Grammer. Evolutionary Aesthetics. Springer Verlag, Berlin, 2003.